Andreas Strehler Cocon

Some watch collectors already know the name Andreas Strehler, however his name is not as widely known as that of the man with whom he recently created the Maître du Temps Chapter Three, Kari Voutilainen.

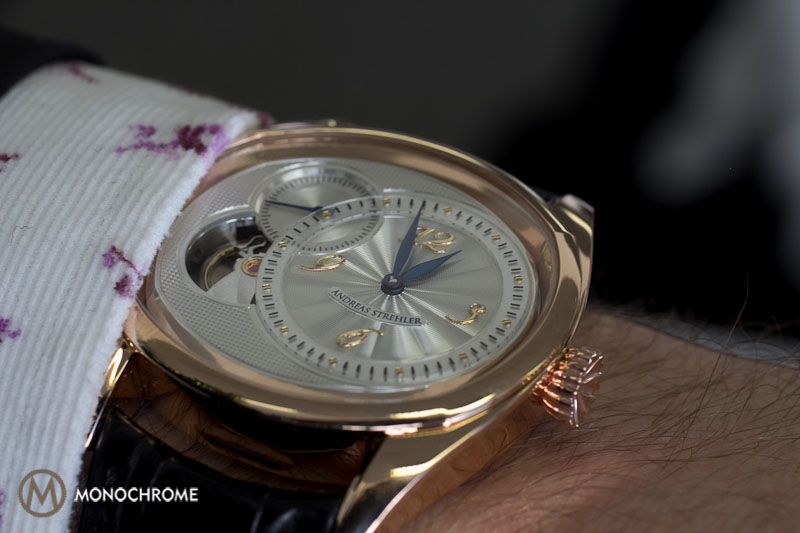

Andreas Strehler is responsable for quite a few well-known watches and recently presented the second watch baring his own name on the dial, the Cocon. Based on his first watch, the Papillon, Strehler was categorized as ‘extravagant’ in this list of independent watchmakers. While the face of his newest creation is rather classic, when turned around it shows one of the most breathtaking bridge designs I’ve ever seen.

The ‘engine’ of the Cocon is a modified Papillon movement with 78 hours of power reserve coming from two main spring barrels. Andreas told me that with the two main spring barrels, the Cocon actually has a power reserve of 90 to 100 hours. However by means of an epicyclic gear set, the two mainsprings are prevented from unwinding further than the mentioned 78 hours.

The reason to cut of the power, is that the the further the mainspring unwinds, the tension becomes less. This would result in a less than optimal chronometric rate, which is no option for Andreas Strehler! By limiting the unwinding of the main springs, Andreas Strehler is able to achieve an almost linear deployment of energy and an optimal power flow and constant precision for the whole time that the watch is running.

Andreas Strehler diverted from the classical movement construction and choose instead a central plate on which he positioned the gear train with its additional seconds-wheel without altering the position of the barrels or the balance-wheel. Let me explain this: spring barrels normally turn too slowly for the display of minutes and too fast for the hours. But in the Cocon the timing works differently. The unwinding of the main spring barrels are firmly tied into the sequence of the movement.

This resulted in a movement design without equals. The butterfly shaped bridge refers to Strehler’s previous watch called Papillon and now the ‘papillon’ is inside its ‘Cocon’. The photo below shows the parallel connected barrels, which guarantee a constant winding and unwinding of the mainsprings. The use of genuine conical gear wheels for the winding wheel and the winding pinion show no wear in the transmission of power and are therefore extremely long-lasting. In addition, their special gear tooth system enables the watch to be wound up smoothly and lightly.

The finish of the papillon shaped bridge, of the cogged wheels and screws, as can be seen above, is of the very highest standards and simply cannot be done by a machine. The Côte de Genève decoration is done by hand and so is the ‘anglage’ (meaning beveled endges). The wheels are also internally beveled, something that also cannot be executed by any machine. What Andreas Strehler shows here is hand finishing ‘pur sang’.

About Andreas Strehler:

After completing an apprenticeship as a watchmaker, Andreas Strehler worked for Renaud et Papi, where he collaborated with great watchmakers such as Robert Greubel, Stephen Forsey and Giulio Papi. In 1995 he became a freelancer and developed numerous movements for well-known watch manufacturers such as Chronoswiss and H.Moser & Cie. Not to forget the Opus 7 he created for Harry Winston and his recent collaboration with Kari Voutilainen to create Chapter Three for Maître du Temps.

The dial’s decoration is done by hand: engine turned parts and a guilloche dial for the hours and minutes. The hands are made of blued stainless steel and around the hour/minute dial and partially overlapping the seconds dial, is a sapphire chapter ring, similar to that of the seconds chapter ring of the Grönefeld One Hertz.

Since Andreas Strehler didn’t do anything the easy way, the case is also not a simple three-part case. The Cocon case is a complex construction with no fewer than 12 elements. Its modular construction makes it possible for customers to choose their individual material combinations and so create their own, personal wristwatch.

However the main reason for the complex construction is to guarantee an optimal restoration of the case of the Cocon (or Papillon) to a condition as good as new, even after many decades. The Cocon’s case is similar to the Papillon case, however it the lugs are shorter to ensure more harmonious proportions on the wrist.

Information about Andreas Strehler’s watches, Papillon and Cocon, can be found on his website here.

This article was written by Frank Geelen, executive editor of Monochrome Watches.

2 responses

Hi Frank,

I have ordered a Sauterelle because I feel that his “constant energy” escapement makes very good sense – compared to the far more technical and expensive solutions that are so “en vogue” these days.

Everything else in the watch is a delight and a dream!

Best to you,

amerix

Congratulations Amery!

Shame on me, I totally missed the introduction of Andreas Strehler’s newest timepiece. It looks as gorgeous as the Cocon, and the addition of a constant force to the escapement makes it even better!